–By Linda Freeman

–By Linda Freeman

The songs we know as spirituals are generally thought of as religious music, but they represented much more to the people who created them. The Africans who were brought to the Americas to provide slave labor came from a society that valued group singing and dancing, making it a vital part of civic and religious life. The villages and tribes came together to celebrate, mourn and recognize major events, thus building a sense of community. In the new life that was forced upon them, they were separated from all that was familiar, forbidden the use of their own languages, and treated as less than human, but they continued to find ways to sing together. New words were applied to old forms to give rhythm to their labors, bond with each other as a new community, and affirm their humanity.

When the African slaves were introduced to Christianity, they naturally applied these new stories and images to their own experience. Their version of worship, and of Christian doctrine, were necessarily different from that of their masters. Sunday morning services were organized and mandated by the white slave owners, and sermons exhorted slaves to meek obedience. Clandestine black-only services were held in cabins, or on the land out of sight of the masters, and featured black preachers who led singing, dancing, and praying well into the night. The worshippers developed signals to alert each other to such meetings; they might sing “Steal Away,” or pin curtains shut to mark the right cabin. Some masters allowed and even encouraged such gatherings; when there was no need to hide, the singing and praying could become quite loud. Once again, the former Africans were singing and dancing as a group, to build the courage and hope they needed to sustain themselves under a brutal, dehumanizing system.

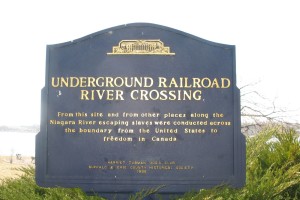

The words of their songs seemed to go along with the approved doctrine of remaining docile and waiting for a heavenly reward; but words can carry many meanings, and the slaves used their music as a vehicle for resistance, subversion, and rebellion. Crossing Jordan and going to Canaan, could indeed mean dying, but it could also mean crossing the Ohio River and entering a free state, or escaping all the way to Canada. Rivers and water are frequent subjects in spirituals; that could serve as a reminder that walking in a stream helps destroy tracks and scent, or that a specific river was a good path to follow. It could also be a reference to Moses leading the Children of Israel out of slavery and across the Red Sea; in that story the water becomes an instrument of revenge, drowning the pursuing soldiers. The story of Joshua, who conquered the city of Jericho with music as his primary weapon, was a fine instance of God favoring the apparent underdog. Gabriel Prosser and Denmark Vessey, who led separate insurrections in the early 1800s, were both know to quote the story of Joshua for inspiration, and surely the song commemorated their stories, and that of Nat Turner, as well as the biblical hero.

“Hold On” provides a good example of a song with multiple layers of meaning. Its steady beat and driving rhythm make it a useful accompaniment to a hard, repetitive job like hoeing cotton or chopping sugar cane. Its refrain “Keep your hand on the plow, hold on, hold on” may sound like nothing more than encouragement to keep working. But if you know that “The Plow” is another name for the constellation Ursa Major (a.k.a the Big Dipper, or Drinking Gourd) that points to the North Star, it becomes encouragement to head north and keep going. The line “Nora, Nora let me come in, the door’s all fastened and the windows pinned” suggests someone arriving at a secret service; it goes on to say “If you want to get to heaven let me tell you how, just keep your hand on the gospel plow” which could mean that the slave preacher was explaining a way to escape. Even if it was not signaling a specific service, or an immediate escape plan, singing this song while working in the fields would have been a reminder that there is something better, and people do make it there.

These songs were created by people with much to overcome; the fellowship they found in their private services allowed them a respite from the weariness, pain, and degradation that made up most of their lives. The need to keep their souls alive with infusions of joy and hope, and the comfort they could give each other in acknowledging the “troubles they’d seen,” were every bit as important and necessary as the plans, signals, and cover they provided for those taking the Underground Railway to freedom. That transcendence continues to shine through this music, along with the anger and purpose that drove people determined to leave free lives as dignified human beings. It spoke to activists in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ’60s; it speaks today to those struggling to overcome poverty, prejudice and violence.

In learning to sing these songs, we, a predominantly white choir, have had to examine a particularly ugly part of American history. We must acknowledge the pain and suffering at the foundations of our country along with the ideals and the glorious visions. The promise of “liberty and justice for all” has still not been fulfilled for all our citizens; the question of just who counts as one of those men who were created equal is not yet answered. Over the centuries, group after group has stepped forward to claim their birthright as Americans, demanding equal status in this land of the free. As we sing this music, we must expand our own spirits to welcome them: the first singers who made the songs, and all those who have come since, regardless of their skin tone or nation of origin. We rededicate ourselves to the mighty dream that one day love may rule our land.